| DENKYEM (Crocodile) |

KINSHIP, MARRIAGE, FAMILY

As an undergraduate I argued vociferously with my professors regarding the utility of the study of kinship. I really couldn't see the point of sitting down with those charts of triangles, circles and squares and worrying about how people "call one another" or "classify" one another. After spending some time with learning to understand how we can idiosyncratically create meaning through combination, I remembered how much I loved diagramming sentences when I was in grammar school and I began to understand that I had a fascination with mathematical patterning and meaning. Intriguingly, the study of kinship brought me to the exploration of what has become one of my greatest passions: the cross-cultural analysis of what we call "mathematical reasoning." In the spring, I will teach a new course called "ethnomathematics," and the root of that "tree" is my investigation of the trees of taxonomic hierarchies and their componential definitions. As kinship guru Rodney Needham has indicated, when we study kinship systems we are looking at the ways in which people formulate propositions in terms of categories. The study of Bolinger's "decontextualization" and of metaphor as the subsequent "recontextualization" of the world has had a strong influence on the way in which I view logic and mathematical reasoning in general.

The courses that I currently teach in logic and symbolic reasoning have their beginnings in my undergraduate and graduate specializations in the study of kinship. Through the study of the work of Rodney Needham, I was first introduced to Wittgenstein, and Hume. In the "transformational analysis" associated with Southwold, I found Frege, Tarski, Carnap, Hempel, Scriven and Robinson and Quine. Through Riviere I investigated Plato and Bambrough and realized once again that I needed to return to the work of Wittgenstein to understand the analysis of kinship. In addition, courses in kinship and linguistics lead to my study what is called "descriptive semantics." "Bounded fields" like kinship terms are wonderful models for developing such analyses.

But the study of kinship isn't all abstraction and conceptualization. It seems clear that formalists like Needham, working at the level of ethnology (cross-cultural analysis) support the analysis of the units and combinatory rules or syntax of symbolic logic as the logical equivalents of kinship studies. However, the history of anthropology (at least in British and American expressions) is one that has, most often, favored inductive argumentation. With that in mind, we investigate the ethnographic (single culture, syncretic) value of drawing descent lines, collecting kinship terms, observing marriage systems, and recording kinship attitudes. In other words, we also turn our attention to what Leach has called the "affective" or emotional aspects of relationships in an African context. I think, however, that the investigation of THESE aspects, will bring us back to a Zande proverb that has been quoted by one of the early masters of the study of kinship, E. E. Evans-Pritchard: "Can one look into a person as one looks into an open-wove basket?" I think that I would answer : "No". So, I prefer to think about thinking.

Text: Joanne Munroe, WCC IDS Instructor

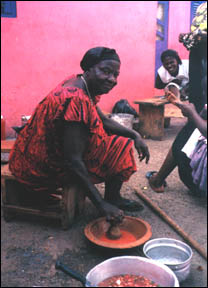

Kumasi, Ghana photo: Kathryn Roe, WCC Art Instructor

|

|

© WCC African Study Project