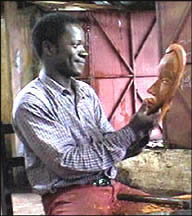

Diallo Mohamed Lamine is a woodcarver like his father before him, a member of the Dan ethnic group with its strong tradition of carving for practical and ceremonial purposes. His home is in Man, a region of mountainous jungle a full day’s journey from here near the Liberian border, and he has come by bus and taxi to stay in this house teaching us. Each day I spend anywhere from thirty minutes to five hours carving with Diallo and a group of six or seven other students. For our first project each of us will carve a pair of Dan-style masks.

I start with a split bolt of heavy, stringy ironwood, glowing a startling shade of red wherever fresh heartwood is exposed; I cut it to rough length with a western-style handsaw and Diallo marks the first shapes crudely with white chalk ("Donnez-moi la craie," at first too fast to understand, then more slowly). The initial shaping is done with a tool he calls a catalet, which is a close cousin to what we call an adze. Elsewhere in the world I’ve seen tools much like this used for all manner of tasks, from the manufacture of dugout canoes to the splitting of firewood; I’ve even used an adze myself a time or two to give an authentic, hand-hewn look to manufactured beams. I have never tried to create anything as small or delicate as these carvings with so crude a tool, but in Diallo’s hands the catalet dances and the chips fly.

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

It does not take long to notice that, crude though Diallo’s chalkmarks may be, to deviate from them by accident or misguided design tends to leave my sculpture looking malformed; misshapen in ways I can sometimes barely see...until Diallo himself straightens my mistake. "C'est bon!" he says, routinely, before making just a few minor adjustments (confidently chopping a fraction of an inch from his fingers, the chips raining down all around), these adjustments making somehow all the difference. I have a reasonable eye, of course, the product of long years in the construction trades, and there are times when Diallo's rough chalk marks seem misplaced to me, skipping along the rough, hand-split grain. At home I'd draw a thin line with a sharp pencil exactly where I wanted it, then split that line with one of a wide variety of expensive tools; at home much of the skill involved in the creation of finely detailed objects consists of knowing how to use exorbitantly expensive power tools. Here, however, I perch my butt on a chunk of ironwood log and hack at my workpiece with the catalet. There have been a number of minor (but bloody) accidents already among the students, but I am reasonably proficient at keeping fingers and sharpened steel separated.

My masks are already recognizable representations of human faces when I set the catalet aside and begin the series of handsaw and chisel cuts which fully define its features. I carve high, smooth-domed foreheads, deep-set slit eyes, strong lips and arching eyebrows; Diallo demonstrates techniques and encourages each of us in turn, fixing mistakes and counseling patience. "Un peu, un peu…Doucement, s’il vous plait," he says. Within a few days "un peu, un peu" enters the household lexicon, and is heard in all sorts of applications, from all sorts of people.

It seems a shame when my chiseling is done and I have to start shaping with the wood rasp. I like the rough-hewn, tooled look left by catalet and chisel, this look being one sign of handcraftsmanship, much prized among woodworkers at home. But I am being instructed by a master Dan carver, and when he says to smooth those chisel marks with a rough rasp I do what he says. The next stage is to smooth out all the marks left in turn by the rasp, using a metal file with its finer teeth, following which Diallo pulls out a set of odd-looking little scrapers—one bent and one straight—and I laboriously scrape and shave away the markings left by the metal file. This takes, essentially, an eternity.

Like most American carpenters I am not much of a woodworker; I am, however, reasonably proficient at hand-sharpening cutting edges. For many years I used oilstones on my chisels, knives and plane-irons, and recently I came to prefer Japanese-style waterstones for their faster cutting action, but in any case the basic theory is the same; you sharpen your tools on progressively finer grit stones until they are razor sharp, and resharpen them often to maintain that edge (the phrase "razor sharp" is not used casually in this connection: a properly sharpened chisel will shave hair cleanly). Scrapers—which produce on wood a tooled surface similar to that left by a sharp chisel but have the advantage of working at odd angles to the grain in a way that chisels are reluctant to do—are sharpened by first filing or grinding a perfectly straight edge, then using a special tool to roll over an invisibly small hook in one direction on the working edge. Woodworkers love to discuss and compare sharpening techniques, and their journals are full of articles on the subject (and full as well of advertisements for expensive gadgets designed to make this arduous job easier). I once watched a crew of Japanese temple-builders at work—by far the most highly skilled carpenters I have ever seen anywhere—and twice a day they all stopped work to sharpen their tools; at great length and very elaborately.

Diallo does not do this; his methods for sharpening tools are—not to mince words—barbaric. A little hand-cranked rough stone perches on the edge of our workbench; it makes a horrible, deafening scraping noise in use, and Diallo uses this grinder periodically when a tool is really dull. But the sharpening tool of choice is the ordinary metal file—in this case, a fine-cut triangular taper file. Diallo takes dull chisels and files them on what all my training tells me is the wrong side of the edge (not on the bevel, but on what is at least initially the flat side of the chisel), sawing rudely back and forth for a moment or two before handing the chisel back to its user. Miraculously, this method of sharpening is entirely sufficient, though this fact calls into question all that I know about the art and the science of sharpening hand tools. Put this newly sharpened chisel to a chunk of heavy, stringy ironwood and tap with the mallet; it cuts cleanly with or across the grain, peeling off shavings and dangling them neatly to one side or another. Worse yet, within a few weeks the crank on the little stone breaks and the taper file gets dull (files, as no one but myself seems to understand, are designed to cut on the push stroke but dull rapidly if not lifted off the cut when they are pulled back in the other direction). I take the (dull) file and saw ineffectually back and forth on the wrong edge of a chisel as Diallo instructs. Nothing changes. Diallo does exactly what I have just done, and by some unfathomable magic manages to produce—without apparent effort—a sharp edge on the chisel. I thank him as humbly as possible and return to my carving. The man is a magician of some sort; a sorcerer. I check surreptitiously to see if I can spot a cloven hoof, a tail, or horns.

|

|

|

|||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

As my hand-scraping progresses, my masks again take on that pleasing hand-tooled look I like so such, and I spend a bit of extra time struggling to get rid of every possible rasped or filed cross-grained scratch. Periodically Diallo sees me struggling with a particularly troublesome facial feature—noses are noteworthy in this respect—and he demonstrates what it is that he wants me to do. He and I do not share a common spoken language (my French is atrocious, the functional equivalent of his English), so I am expected to watch closely and imitate what he does. Of course I fail to do this time and time again; I am a user of words, and my observational skills have (it is abundantly clear) atrophied from lack of use. In any case, Diallo’s skill with these little scrapers is almost beyond my comprehension; in his hands they scrape smoothly, carve like chisels and slice like knives…all with grace and apparent ease. I push my nose in as close as possible, watching what he is doing, and then do my clumsy best to imitate.

By the time my masks are fully scraped smooth, again glowing softly red in the shade of our little workshop, the next step is obvious; I am to wrap my fingers with rough sandpaper and make these smooth glowing surfaces dull and scratched once again. At first I am careful to sand everything in the direction of the wood’s grain—it is not for nothing, I tell myself, that I once instructed small children in the making of birdhouses and toy boats at summer camp—but it becomes clear that this is not possible, and in any case not part of the program here in Diallo’s class. When all surfaces are dull and full of scratches in random directions I move on to a finer sandpaper, this grit designated #220 for the size of the abrasive particles embedded in its surface (the number corresponds, loosely, to the number of sharp bits of silicon carbide which when placed in a line would measure a single inch; #220 sandpaper is rather fine in texture, and progress is painfully slow). I grumble and curse each individual cross-grain scratch I made with the rougher paper; I try to pretend I am engaged in some sort of arcane meditative practice; I sing spritely, upbeat songs; I lapse into lethargy.

It will come as no surprise to hear that Diallo is highly accomplished at this phase of woodcarving too. Sometimes when I am weary of scratching away at the same spot with my little worn-out scrap of #220 sandpaper without apparent results he takes over for me for just thirty seconds or a minute; in Diallo’s hands the same dull, used-up sandpaper instantly raises dense clouds of dust, and the most resistant imperfections in my mask’s surfaces seem to melt away and vanish. He has a way of holding the paper, a way of holding the mask, a way of focussing his energy…we all notice this, but none of us seems to quite understand what he is doing, much less how we might do the same ourselves. Eventually I move on to the last grit of sandpaper: #600. This is the sort of paper used to apply finish to fine furniture, and it offers hardly any resistance when slid across the wood. I am creating no dust and eliminating no visible scratches, but where I rub this sandpaper across the surface of my mask it is left velvety smooth. This step, fortunately, does not last nearly as long as the last, and I am soon done.

All across sub-Saharan Africa you can wander the dusty streets behind the curio stalls and tourist hangouts and stumble across the people who make the sculptures that are sold to the unending streams of tourists; I've got a couple myself, propped casually atop piles of books and hanging on little rectangles of plasterboard between bedroom and bath. Everywhere there are armies of boys squatting in the heat working little scraps of sandpaper...and more armies rubbing in the dark Kiwi shoe polish that serves as the universal stain and polish here as it does elsewhere. I am not now one of these boys, of course; but yesterday I set aside my tiny sandpaper scraps (the tips of my fingers feeling a bit sensitive, I admit, and the tendons in my hands aching) and dipped a little bristle shaving brush into the can of shoe polish and started wiping it on my first carvings. The stuff has an undeniable appeal; it fills minor surface scratches, stores and travels well, buffs out easily and a little bit goes a long way. I think that I am beginning to understand how this all works.

I am beginning to understand also that there is immense skill, acquired at some cost in time and suffering, in even low-grade carving—by which I mean the dark, clunky stuff for sale throughout the world wherever there are tourists and unemployed locals. Diallo has a few apprentices in his shop back in his hometown, and one of our group went there for a visit; she says they had already been hard at work when she arrived each day at 7 AM, and that they worked into the evening each day. I imagine myself a boy in my early teens, waking up before first light to dust the shelves of Diallo’s shop, scraping and rasping and sanding countless carvings year after year, happy to be working for Diallo, happy not to be one of those boys rubbing on kiwi polish anonymously, squatting in the gutters on the streets of the capital.

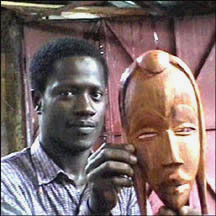

One day I bring some photos home from the developer, and I show Diallo some shots of old masks taken in a museum in Paris. He flips through the stack calling out names of ethnic groups—Baoulé, Senoufo, Lobi, Ashanti—sometimes pausing to praise one or another for its workmanship (though truthfully, most of my photos are difficult to make out clearly, having been shot in dim museum light without a flash, handholding my camera at absurdly slow shutter speeds). There are photos of carvings from French Polynesia and New Zealand mixed in, and Diallo dismisses these with hardly a glance ("Ce n’est pas d’Afrique!"), although some huge slit drums hold his interest briefly. He picks out a Dan mask immediately, and is clearly excited to see it. Here in Africa, in this ceaseless heat and humidity, a thirty-year-old mask is considered quite ancient; this photo shows an outstanding Dan mask of precisely the type we have been carving…but perhaps a hundred years old, carved long before the advent of sandpaper or Kiwi shoe polish, by someone certainly distantly related to Diallo himself. "C’est belle," he says, "C’est trés, trés belle," and there is real emotion in his voice. He points to the hand-tooling marks around the edges of the piece, which I, ex-carpenter that I am, had not noticed. I have another print made from the negative and give it to Diallo.

Our original plan was that Diallo would join us for the first week or two of our time here, returning again for our final week, but somehow it develops that he will remain in residence more or less non-stop for the duration of our stay. My masks finished, I start on a pair of Ashanti-style akuaba dolls, traditionally carried by women of this Ghanaian kingdom to ensure successful pregnancies and attractive children . As woodcarving projects the akuaba figures are notable for their fragility; arms, noses and eyebrows have a distinct tendency to split out and fall off at the slightest provocation…or, at least, I see this happening all around me. Quite a bit of glue goes into some of our Ashanti dolls; mine remain whole, though one has a distinctly lopsided cast to it. In due course I am again torturing myself with tiny scraps of #220 sandpaper, and rumor has it that a few students even neglect to bother with the final #600 sanding, proceeding instead directly to the little tin of Kiwi polish.

The next project is a set of five elephants. It is not clear to me why these need to be carved in sets of five, and indeed given what I now know about the amount of work involved in a production run of just two items, five elephants does seem quite ambitious. It is obvious, however, that this is non-negotiable, and I take another long split bolt of ironwood and begin crosscutting at Diallo’s chalkmarks.

Now, the alert reader will have previously noted that every elephant arrives in the world fully equipped with a long, thin trunk, a pair of rather delicate ears and four knobby legs. Carvings of elephants possess all the same attributes, and they are not over-endowed with square, parallel surfaces by which one might clamp them to a workbench while chiseling, sawing, rasping, filing, scraping or sanding. In fact, these carvings are quite prone to falling out of the vise when clamped in a necessarily gingerly fashion just behind the ears or across the butt, and this tendency to slip out of the vise combined with their abundance of fragile features leads to an unusually high rate of mortality among elephant carvings. All around me as I work elephant families are decimated; trunks are snapped off, ears lost in an instant to slips of the chisel, legs broken by falls on the hard concrete floor. Somehow my set of five continues to take shape, without any serious mishaps so far...but I have not yet started sanding their intricate little (fragile) body parts.

Still to come: dancers, impalas, pirogues full of fishermen, giraffes.

November, 2000 - Mark Harfenist

Photos of Students by Mark Harfenist