ART and MUSIC - Anansi Travel

ART and MUSIC - Anansi Travel

Art:  In recent years it has become apparent to students of African Art that in order to understand the inherent complexities present in most African works of art, it is necessary to consider both the perspectives of the conventional Western assumptions and the indigenous perspective. This presents problems because it is difficult for Westerners to fully understand the indigenous perspective given the longstanding Western imperialistic involvement in Africa. In the traditional discipline of art history, the importance of African art has been long relegated to the role of catalyst or raw material for the creative genius of Western artists such as Pablo Picasso. However, with Susan Vogel leading the way with her Baule, African Art; Western Eyes, we are beginning to take steps toward a new look at African art - one which appreciates the methology in Western art history, but also considers the complexities of the visual art traditions of the peoples of Africa.

In recent years it has become apparent to students of African Art that in order to understand the inherent complexities present in most African works of art, it is necessary to consider both the perspectives of the conventional Western assumptions and the indigenous perspective. This presents problems because it is difficult for Westerners to fully understand the indigenous perspective given the longstanding Western imperialistic involvement in Africa. In the traditional discipline of art history, the importance of African art has been long relegated to the role of catalyst or raw material for the creative genius of Western artists such as Pablo Picasso. However, with Susan Vogel leading the way with her Baule, African Art; Western Eyes, we are beginning to take steps toward a new look at African art - one which appreciates the methology in Western art history, but also considers the complexities of the visual art traditions of the peoples of Africa.

Although great attention is paid by artists and artisans of West Africa to the aesthetic qualities of their art works, the quality of the work of an African art object is rarely, if ever, the primary consideration. The most important aspect of an African work of art is it’s function. It may be used to assist with a connection to the spirit world, a religious function; it may be used to commemorate an important event, a political, social or religious function; or it may be used for monetary gain in a modern day market place. The quality of the aesthetic attributes of a work of art varies depending on the skill of the artist, the attention to the work and the materials at hand. Whatever the general or specific use of an art object, it's function is primary to most West African people, and the aesthetic qualities, although also important, are secondary.

In most African languages there is no word for “Art.” Art is not separate from function, and as a result is interwoven with the lives of African people in an intimate and meaningful way. Susan Vogel tells us in her 1997 book, Baule, African Art; Western Eyes: “ Late in the course of the research and of our decade-long discussion, Nguessan summed it up: We live with art in the sense that statues are kept in our houses, but we don’t do it in the way they do in America. We live with the spirits more than with the statues. . . you will never hear a Baule say, “This is beautiful,” because that is not what they are looking for in the statue or the mask. Even though it is beautiful. We are aware that Baule art is beautiful, but the aspect that interests us the most is the spiritual, religious side.”

Music: Generalizations about African music are difficult due to the cultural diversity of the continent's peoples. The sub-Saharan region of Africa has several thousand peoples, each with different customs and religions (the small country of Ghana has over 60 ethnic groups). Over 700 languages or dialects and geographical conditions contribute to the wide variety of musics in Africa. The traditional music of one tribe may differ substantially from the music of another tribe only a short distance away - music that is vital to one group might make little sense to a neighboring group.

Among all of this diversity, however, are some common features. Most traditional African music is functional and permeates African life - it is more than aesthetic expression. Songs are used for religious ceremonies and rituals, to accompany work and other daily activities, to mark the stages of life and death, to educate, to recount history and current events, to provide political commentary, and to provide moral guidance. Of course music also serves to entertain. Dance is an integral partner to music and is used in rituals, worship, celebrations, and recreation. Often the dancers are simultaneously singing or playing drums. They may also have rattles tied to their wrists or ankles. Because most African music is functional, there is often little distinction between the performer and the audience - spectators may become part of the performance. Few are passive observers when African music is performed.

Africans have strong beliefs about the status associated with particular instruments and with the spirit of an instrument. In Ghana and many other regions, drums symbolize power and royalty. The number of drums owned by a chief might be indicative of his place in the societal hierarchy. The drum carver and the master drummer (the leader of an ensemble) are both highly regarded. When drums are constructed, rituals are performed so that the spirit of the tree will live in the drum (in one ritual, the tree is given an egg, three leaves, and libations!). Some drums are regarded as the property of a group rather than an individual, are housed in shrines, and are offered sacrifices.

Rhythm and percussion are highly emphasized in African music. Polyrhythms (several different rhythmic patterns occurring simultaneously) are a predominant feature. Rhythm in African music has evolved to be much more complex than rhythm in Western music. Music once considered "primitive" by Westerners is now highly regarded for its rhythmic sophistication and complexity.

Other common features include the use of improvisation (using rules and guidelines), the predominance of fast tempos, and the use of iterative forms. Music often uses a call-and-response allocation of performers (one of the African influences prominent in jazz). African singers perform using a wide variety of sounds. The singing style is typically loud, open, and resonant but may also be tight and constricted. In addition, singers may make other vocal sounds such as whispers, grunts, and shouts. The use of a wide variety of tone qualities is also characteristic of African instrumental music. For example, bottle caps are often added to the mbira (thumb piano) to create a buzzing sound. African music is transmitted orally from parent to child or from teacher to student. Performance practice and compositions are learned by rote.

As with the word art, the abstract word music - with all of its Western connotations - is not used by many African peoples (although there are words for song and dance). Because the music is primarily functional, musicians are concerned with the impact of the music. They do not care if the music is considered "beautiful" in the "Western" sense.

|

FUNTUNFUNEFU-DENKYEMFUNEFU (Siamese crocodile) |

These reptiles share a common belly yet they fight over food. This symbol signifies the unification of people of different cultural backgrounds for achieving common objectives despite their divergent views and opinions about the way of life. The symbol stresses the importance of democracy in all aspects of life. It also encourages oneness of humanity. It therefore discourages tribalism. This is a symbol of democracy and unity in diversity.

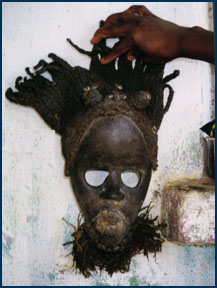

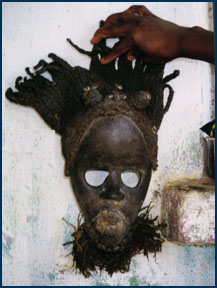

Art Text and Côte d'Ivoire Dan mask photo: Kathryn Roe, WCC Art Instructor

Music Text: Brian Palmer, WCC Music Instructor

email: anansitravel@yahoo.com

© Anansi

In recent years it has become apparent to students of African Art that in order to understand the inherent complexities present in most African works of art, it is necessary to consider both the perspectives of the conventional Western assumptions and the indigenous perspective. This presents problems because it is difficult for Westerners to fully understand the indigenous perspective given the longstanding Western imperialistic involvement in Africa. In the traditional discipline of art history, the importance of African art has been long relegated to the role of catalyst or raw material for the creative genius of Western artists such as Pablo Picasso. However, with Susan Vogel leading the way with her Baule, African Art; Western Eyes, we are beginning to take steps toward a new look at African art - one which appreciates the methology in Western art history, but also considers the complexities of the visual art traditions of the peoples of Africa.

In recent years it has become apparent to students of African Art that in order to understand the inherent complexities present in most African works of art, it is necessary to consider both the perspectives of the conventional Western assumptions and the indigenous perspective. This presents problems because it is difficult for Westerners to fully understand the indigenous perspective given the longstanding Western imperialistic involvement in Africa. In the traditional discipline of art history, the importance of African art has been long relegated to the role of catalyst or raw material for the creative genius of Western artists such as Pablo Picasso. However, with Susan Vogel leading the way with her Baule, African Art; Western Eyes, we are beginning to take steps toward a new look at African art - one which appreciates the methology in Western art history, but also considers the complexities of the visual art traditions of the peoples of Africa.